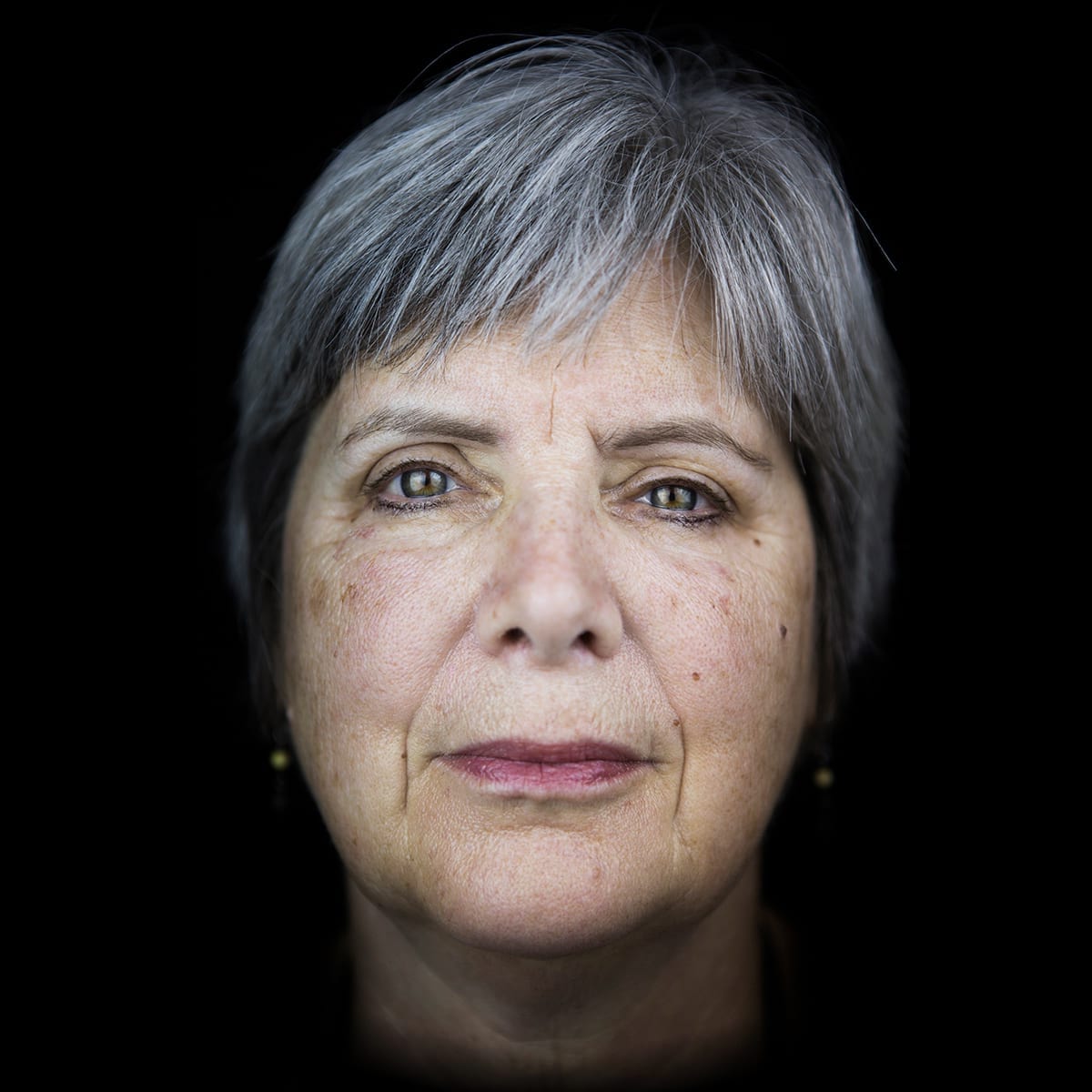

Uthpala Eroshan

Born July 6, 1986 – Colombo, Sri Lanka

As a child in Colombo, the capital of Sri Lanka, Uthpala Eroshan grew up steeped in the Kandyan tradition of dancing and drumming. “[When] I was a little kid, I like to listen to music, and I like to see dancing. I was in the school at grade 6th; we had to choose one art subject, and I choose dancing, and did dancing for four years.” He and his group of middle-school friends participated in both athletics and Kandyan dancing, and for Uthpala, dancing was a natural extension of his social life, “Because I love my friends.” His schoolmaster later gave him beginning lessons in the accompanying drums, and he took to them with great ease. “These artistic things is very familiar to me…my father, he’s a painter, and he did Indian music. He played Indian drums and…you know, the guitars and the violins, that kind of thing. I think that the reason, another reason, I love the artistic things.”

After high school, Uthpala went on to study Kandyan drumming with his guru Ravibandu Vidyapathi. His guru had a school and there Uthpala eventually became a teacher of drums to children. He also performed all over Sri Lanka with Ravibandu and worked as a member of the Naadro band. “It is a very famous percussion band in Sri Lanka. I met there Rakita Vikramnata. He’s one of the finest percussionists in Sri Lanka…he is a very talented guy. I work with him like eight years, and he gave me the opportunity to learn of a lot of different music styles, especially Latin music and Indian music, and I play lot of varieties of drums with him, and I traveled to a lot of countries for drum shows, and at that time, I met lots of artists from different countries. I learned a lot of good things and a lot of artistic things.”

When Uthpala talks about drums and drumming, a great smile spreads across his face. When asked why, his response is, “Actually, when I’m playing, I can express myself. What I am thinking is coming to my hands, and I can show to others that is that what I think.” Uthpala knows that when he plays Kandyan drums, he is participating in a venerable and ancient tradition but that he is also contributing something of his own spirit from present times. Even as a bearer of tradition, he is also able to add something of the personal. Ultimately, however, Kandyan dance and drumming is done for others, for the people, for the King, for the Gods and for Lord Buddha.

Uthpala is now a guru of drumming himself, and as such, he understands music education in a spiritual sense. When asked what he is trying to teach, aside from the mechanics and techniques of playing the instrument, he replies, “If we learning Kandyan dancing or Kandyan drumming…the first thing is to respect each other and the elders…We ask for a blessing from Lord Buddha…from the gods…from the gurus… Second is discipline. If we don’t have discipline, we can’t do dancing or drumming.” Traditionally, gurus would have students doing all sorts of tasks prior to actually playing the instrument so as to develop concentration, attention and patience. In America, this procedure is harder for people to accept, and so Uthpala moderates and tries “to do a little bit of that discipline and respectable things to teach them.”

Uthpala makes sure to emphasize that Kandyan dancing and drumming is an oral tradition, “if we want to do Kandyan dancing, [to begin] we have to choose a good teacher because this is not written; we don’t have written history of Kandyan dancing; it’s coming from by mouth you know…You have to choose the best guru.” Drumming, in particular, has always been deeply embedded in Sri Lankan culture. For instance, “In ancient time, if King needs to give message to people, he has a drummer; his name (title) is Anabera Penyeki. King tell him the message and that Anabera Penyeki goes village by village. He play the drum and people know the King’s message came…and they go to that place and listen to the message.” Here’s another example: At the New Year celebration, a big drum is used; seven people can play it at the same time. At first the elders must “warm up the drum.” They begin by playing and “singing the rhythms, very beautiful rhythms.” Then the younger ones can follow.

Actually, when I’m playing, I can express myself. What I am thinking is coming to my hands, and I can show to others that is that what I think.

Kandyan drums are constructed in a prescribed manner. Particular woods are used as are skins chosen for their particular tones. On a double-sided drum called Gata Baria (oval drum), cow skin is used on the left side and goatskin on the right. Originally, the skins were from monkeys and deer, but the government no longer allows that. In addition, the animals must have died a natural death in keeping with the Buddhist tradition of not killing animals for food or use.

Uthpala was asked to describe his understanding of the meaning of being an inheritor of tradition and of Kandyan tradition in particular. This is his reply:

“An artist is somebody who brings happiness not only to themselves but also others. I think that any person who does something artistic is a person who has peace in their mind. I can say that I’m genuinely happy about being somebody who has skill that not many people have. I want to share with people; that why I do what I do, whether it’s teaching, doing workshops or other shows. I want to share the happiness that I feel when I am dancing and drumming with the rest of the world. I believe that people who have beautiful and peaceful minds make the world beautiful. This is my thoughts, and I tell it to Sumudu [my friend], and she translate it for me.”

Direction/Editing: Mauricio Bayona & Naomi Sturm

Photography: Diana Bejarano

Sound: Camilo Correa

Writing: Paul Sturm

Translation: Dasuni Perera